3 Proven Tips to Help You Perform Under Pressure

Three hacks to try with everything from a work presentation to a wedding speech.

Dr. Hendriksen is a clinical psychologist who helps millions be their authentic selves through her award-winning podcast, which has been downloaded over 5 million times, and in her clinic at Boston University’s Center. Her scientifically-based, zero-judgment approach is regularly featured in Psychology Today, Scientific American, Huffington Post, Business Insider, Quiet Revolution, and many other media outlets. The Savvy Psychologist was picked as a Best New Podcast of 2014 on iTunes and was Otto Radio’s Best Healthcare Podcast of 2016. Dr. Hendriksen earned her Ph.D. at UCLA and completed her training at Harvard Medical School. She lives in the Boston area with her family.

Pressure

excessive or stressful demands, imagined or real, made on an individual to think, feel, or act in particular ways. The experience of pressure is often the source of cognitive and affective discomfort or disorder, as well as of maladaptive coping strategies, the correction of which may be a mediate or end goal in psychotherapy.

Pressure. It pushes down on me, presses down on you, and makes us second-guess everything from how to shoot a free throw, what to say next in an interview, or pronounce “niche” (or is it “nitch?”)

Even if we’ve done a task a million times, like walk up the stairs, order from a menu, or tie a sheepshank knot, under pressure or observation, we get psyched out and lose the most basic of skills. Indeed, a friend told me that once, during a lunch interview, she overthought how to swallow and had to sit for a few moments with a mouth full of iced tea before she could collect herself and figure it out.

How to prevent your brain from shutting down under pressure? Whether you’re trying to nail a work presentation, sink a putt, or spell “bougainvillea” for the win at the National Spelling Bee, let’s get it done with these three tips:

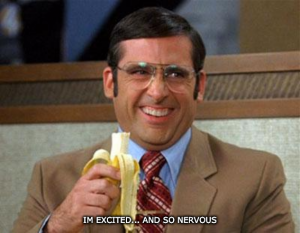

Tip 1: Get excited.

The researchers behind a hilarious but solid study in the Journal of Experimental Psychology made participants sing the opening lines of the iconic song by Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin.”

But right before the part “small-town girl took that midnight train”, each participant was assigned to say a specific phrase out loud, and—importantly—to do their best to believe it. The phrases? “I am anxious,” “I am excited,” “I am calm,” “I am angry,” “I am sad,” or no statement at all.

Next, voice recognition software scored each karaoke performance on volume, pitch, and note duration.

What group performed worst? Yep! you guessed it: the group that said, “I am anxious.” that makes sense…

But who performed the best? You might think it was the group that stated, “I am calm.” That’s often what we try to tell ourselves before a big moment, whether through deep breathing or other relaxation attempts. But instead, the group that did the best belting out before the part “where that city boy was born and raised” stated: “I am excited.”

Why does this make a difference? Before a big moment, we get physiologically activated. All bodily systems toggle to “go.” Even if we tell ourselves to calm down, it’s difficult to slow a racing heart and jangling nerves.

Rather than trying to change our physiology, we can change our mindset by saying “I am excited.” This shifts the task from a threat, which results in anxiety, to an opportunity, and one we’re excited about, at that. Seeing the task as something we get to do, rather than something we have to do, subsequently improves our performance. After all, everybody wants a thrill.

Tip 2: Get a grip (using a ritual).

Back in the days of The Colbert Report, host Stephen Colbert had a distinct backstage ritual before going onstage to tape the show. He’d ring a bell in the studio bathroom, listen to his producer say “squeeze out some sunshine,” touch the hands of each person who worked backstage saving the prompter operator for last, chew on a type of discontinued Bic pen, and finally, slap himself in the face twice.

Much less complicated, but no less scripted rituals occur in all kinds of sports. Take golf: Tiger Woods had a pre-putting routine that lasted precisely 18 seconds: check alignment, adjust feet, two looks at the ball, and then putt.

Or All Black Newzeland national rugby team world-famous Haka. The haka is commonly known as a war dance used to fire up warriors on the battlefield, but it’s also a customary way to celebrate, entertain, welcome, and challenge visiting tribes. The dance introduced in 1888 by New Zeeland’s first representative team, was a tradition of the Māori people of New Zealand to display a tribe’s pride, strength, and unity.

Colloquially, people sometimes refer to pre-performance routines as OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) but the two types of rituals are quite different. A true OCD ritual—the compulsion—is performed in response to an anxiety-provoking thought—the obsession. The purpose of the ritual is to neutralize anxiety.

By contrast, the purpose of the pre-performance routine is to regulate physiological arousal, focus concentration, and put the body on autopilot so it can execute a move that would be hampered by overthinking.

Despite that the scientific jury is still out on exactly how it works, the truth is that all this bouncing and muttering and knee-bending and kiss-blowing makes the magic happen.

So until then, go ahead and try it. At worst, you buy yourself a quiet moment. At best, you’ll reap the benefits of improved concentration and a smooth entry into your move.

Tip 3: Get nodding.

From a study in the Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology comes a subtle yet powerful move, literally.

The researchers asked 150 CrossFit members to participate in a study ostensibly about the use of headphones while working out.

BE COMFORTABLE, BE CONFIDENT, BE YOU.

KEY TAKEN POINTS

- Traditional coping techniques encourage us to change our physiology in a high-pressure moment. Instead, try changing your mindset.

- Even though the mechanisms of action of pre-performance rituals are unknown, they can have a positive effect on performance.

- Physical movements of affirmation or refutation can amplify or neutralize self-talk.